In his book A Night in Buganda, Tales from Post-Colonial Africa (2014: http://robertgurney.com/anightinbuganda/), consisting of one hundred and forty-four tales, the author struggled to make sense of the years he spent in Uganda in the nineteen-sixties. Democracy in that newly independent country was moving inexorably towards dictatorship. You could feel it happening. He and his fellow aid workers were told they were doing a good job but doubts assailed him. Things were falling apart. Was the effort invested about to be wasted?

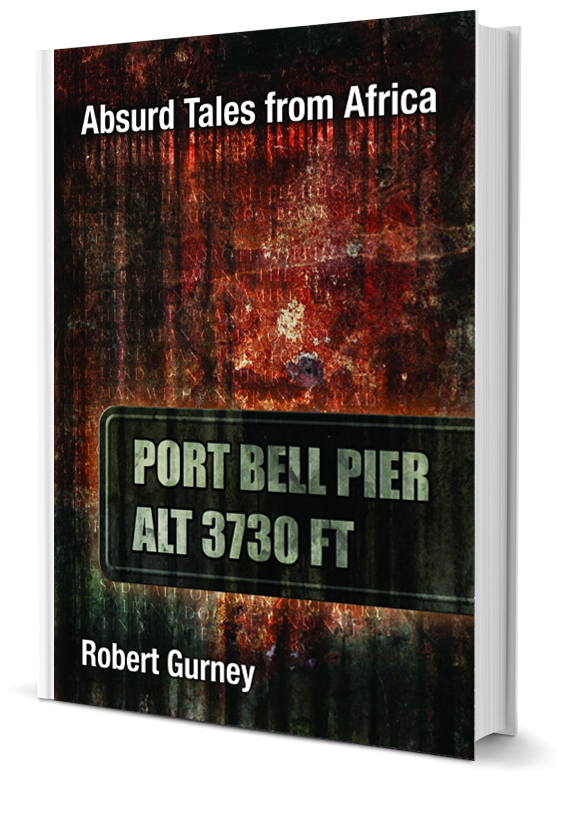

Writing the first book helped him to put some of the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle together. In this book, Absurd Tales from Africa, Cambria Books, 2017, he makes no such attempt to go any further. He explores gleefully the genres of the grotesque and the absurd. The reader is invited to go with the surreal flow and, perhaps, to enjoy the humour.

BUY: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Absurd-Tales-Africa-Gurney-Robert-ebook/dp/B06XDCPG2D

or

http://www.cambriabooks.co.uk/product/absurd-tales-africa/

Johnnie Morris: 2021

I am currently greatly enjoying your books. I generally dislike short stories, but these are, if I may say, interesting, clever and amusing.

Johnnie Morris was a colleague of mine in East Africa. He went on to develop a high profile in overseas in ODA (now Ddid) aid programmes in Kenya and Malaysia. He and his wife Sallie live in Kew, Richmond, Surrey.

Anne Theroux: 2018

I very much enjoyed Absurd Tales. [ … ] the stories are gems. Each one gives glimpses of life in East Africa – strange people, amazing sights, extraordinary events in which the real slips effortlessly into the surreal. The brilliant punchlines make it tempting to speed through to the end of each tale, but I resisted the temptation because there was so much to relish on the way. I am now starting on Bat Valley.

Anne Theroux worked on the same aid programme as the author in the 1960s. She went on to work for the BBC World Service.

Sarah Oubridge: 2018

Your writing is beautiful [ … ] .

Sarah Oubridge lives in London. She works in Marketing. She is the daughter of a close friend of mine at St Andrews University.

Niall Herriott: 2014

“I enjoyed Absurd Tales, not only for the zany humour and the wildly imaginative scenarios but also how the characters and settings for the stories reminded me so vividly of those times.”

Niall Herriot, County Cork, is an Irish writer who was in Uganda with me in the 1960s.

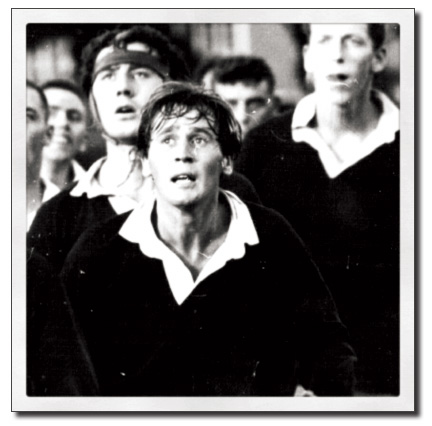

Behind and to the author’s left, top right of the picture, is Charlie Barton from Overton Village, above Port Eynon, in the Gower Peninsula, Wales.

Martin Ryan: 2017

I got delivery last week of three copies of Absurd tales from Africa, and have forwarded two of the copies to a couple of friends from the 1966-67 Dip Ed course.

I very much enjoyed the tales. Erudition lightly worn and affectingly displayed. Where did your wide range of general knowledge from?

It was a rich nostalgia trip to re-visit old watering holes like the City Bar and the Gardenia. [ … ]

Have you read any of the Irish humourist Flann O’Brien / Brian O’Nolan (At Swim Two Birds / The Third Policeman etc)? He wrote Keats and Chapman, a regular newspaper column treating those two literary greats as contemporaries who meet and tell shaggy dog stories. Keats and Chapman has been published in book form.

You are a practitioner in a noble and notable tradition.

And finally, I’m scratching my head about the cover and its hidden meaning / pun. Can you throw me a lifeline on this?

Martin

Martin

Galway pier for example is not at 3000+ feet in the air. It is 0 ft. In the story ‘The Frighteningly High Pier of Port Bell’ Clint or Dave suffers from vertigo when he sees the notice proclaiming the height of the pier. He has to launch the werry. He imagines a 3730 foot drop. He panics. It’s a sort of visual gag.

Bob

(Emails, extracts, 28, 29 March 2017)

Martin Ryan lives in Dublin. He did the Dip. Ed. at Makerere (1966-’67) and then taught

in Kenya for four years, first at Kagumo High School and then at Meru High School.

His final two years teaching in Africa were spent in northeast Nigeria in the mid 1970s.

Jonne Robinson: 2017

Thank you for Absurd Tales from Africa which I thoroughly enjoyed. The pieces were clever and witty. While my knowledge of Kampala and Uganda in the good old days is limited, anyone who was in East Africa back in the day can relate to the atmosphere portrayed in the stories.

Jonne Robinson is originally from New York. B.A. Manhattanville College, M.A.T. University of Massachusetts. Joined TEA. Taught at Mpwapwa Secondary School. After a period teaching and social working in Vermont, moved to England and thence to Malawi. Taught part time at Malawi Polytechnic, also “lady editor” at Malawi Correspondence College. For many years social worker specializing in work with ill and disabled people. Since retirement interests have included reading, writing, archaeology, walking and travelling.

Chris Jones: 2017

“Really enjoyed your Absurd stories from Africa!”

Chris Jones, publisher, Cambria Books, Llandeilo

Annie Davison: 2017

The beauty of these Tales lies in the wonderful pictures created in my imagination, easily competing with any interest I have in mobile phones. The humour arises when life goes wrong for people in serious situations, a bit like John Cleese in Fawlty Towers, immensely watchable. Tales that stand out and I continue to think about are:

‘The Girl with the Glass Eye’, which has a startling conclusion, more so because the man in the story is so shy and naive.

‘The Dead Ringer of Rubaga’ is hilariously ridiculous. That anyone should be able to produce harmonies in this way,succeeding against such overwhelming odds, is truly amazing! A short film produced from this story would be riveting, as would one on‘The Bell Ringer of Montmartre’.

‘The Ghastly Soroti Coffin’ is an unbelievable story; that a coffin should chase anyone is horrific.

‘The Hills of Uganda’ sets off fairly normally until it involves a nudist colony and ends with ‘The Hills are Alive with the Sound of Music’.

‘The Lord of Nyamuliro’ is fantastic; fancy inventing a contraption that fits over a dog’s nose, that turns a bark into a quack! There are metal detecting sandals and full body contraception. But the inventor makes a fatal error, oh dear!

What would it be like to be ‘The Man with the Orange Head?’ How surreal and how did it happen?

‘The Optometrist of Owino’ is a gripping tale of how what you collect could be your undoing.

I loved ‘The Sad Tale of Rwenzori Rory’, in which an intrepid explorer lures the reader in, and ‘The Talking Dog of Kisenyi’ where a man goes in search of talking animals; it seems impossible, in fact most people think it is, until a talking dog is found, at a cheap price, with a twist at the end.

Set against a serious background, in ‘The Tin Man of Nakasero’ metals are welded to someone’s body, yes, I did suspect this wouldn’t go well, made more absurd by the man in the metal becoming a star, and wanting the Presidency! Short lived fame was crushed, oh dear… .

Annie Davison, studied English and Art at Mather College, Manchester, now living in Doncaster. 9 March, 2017.

Annie Davison

“These tales are so funny. I’m also laughing at myself as I only just acquainted myself with Kindle and had assumed the book came through the door.” Facebook message, March 2017.

Clive Mann: 2017

“Bob Gurney’s latest contribution to African literature.”

Tore Rose: 2017

“I read all the stories; only two escaped me completely, the rest were good groaners.

One was the orange head. It still seems too simple! There’s something I dont get obviously, even after saying it aloud. And I’ve never been keen on genie wishes because the only logical wish is “that all my future wishes will come true” – flexibility!

The other was the shaggy dog. Again, too simple and where’s the joke? (And a plot that turns on replacing a beloved pet with a copy is just not on – so it HAS to be funny but I cant find it).

So please explain those two !!!!

Talking dog was one of the best! Hugh was good.”

cheers Tore

Morning Tore

Many thanks for the feedback. I really appreciate it.

The essence of a ‘good’ shaggy dog story is a to have a total anticlimax* at the end. The more of a let-down there is, the better. (The worse it is, the better, if you know I mean? Ricky Gervais teeters on the edge of that at times perhaps.

The first shaggy dog story on record, they say, involved someone saying, after an epic search for an adequate replacement for a lost shaggy dog, “Sorry, it’s just not shaggy enough. Take it away!”

The story builds the reader’s expectations up and then lets him or her down with a bang. The ‘greater’ the absence of sense at the end, the less sense it has, the more intense the nonsense (if that’s possible!) the more ‘shaggy’ it is. That’s the nature of the genre.

Those two stories you mention, ‘The Man with an Orange Head’ and ‘The Original African Shaggy Dog Story’ disappear off the radar, as far as sense is concerned. They leave the reader totally confused. How can a simply told tale (in term’s of language) lead to such a disastrous ending, to such a collapse, to such a disappointment of expectations? How can a pompous man’s trousers falling down be funny? How can an serious woman losing her skirt when a taxi drives off with it caught in the door make us laugh? How can intense human activity, a search for an ideal dog, leading to a flat rejection of the result of the searcher’s efforts make us smile? Cry, perhap but not laugh? There’s a theory that ‘before Civilisation’ we used to laugh at men in suits slipping on banana skins. At Makerere we were taught that such laughter was not bad. It was the product of ‘nerves’. I once stopped a game of football I was refereeing in Kampala when the boys laughed at an oponent who was writhing in agony on the ground with a sprained ankle. Then I remembered our Psychology lecturer’s advice. I dismissed the theory that laughter is a cry of triumph uttered when a rival, another (an other) is rendered powerless.

Some say there is an implosion of meaning in contemporary society.

In the stage of capitalism through which we are living at the moment, you come across it every day. (Please don’t think I am being anti-capitalist by criticising an aspect of it. Capitalism ‘delivers the goods’ to many, more, some say, than Communism did. Many, most, here, are happy with it, with their shopping malls, their DIY stores, their palaces or cathedrals of consumerism. I like them! I am not ashamed to say so.)

I drive past Stonehenge on my way to my younger son’s farm house on the Devon/Dorset border.

Not far away from the monument is a small business/industrial park called Solstice Park. Solstice Park! How did that get planning approval? Here is the statue that draws your attention to it:

Post-modern advertising can empty culture of meaning.

Post-modern advertising can empty culture of meaning.

* Anticlimax:

noun

1.a disappointing or ineffective conclusion to a series of events, etc.

2. a sudden change from a serious subject to one that is disappointing or ludicrous

3. (rhetoric) a descent in discourse from the significant or important to the trivial, inconsequential, etc.

What do you think? I need to brush up my reading on theories of laughter, Le rire etc,

Cheers

Bob

Tore Rose works on United Nations Development Programmes. Tore Rose’s mother thinks he saves the world. And if that doesn’t work, he consults on post-conflict and post-disaster. He lives in France.”

Absurd Tales from Africa was launched in The Princess Louise, 208 High Holburn, London on Wednesday, 22 March, 2017. A reading of the stories ‘The Fiendish Uganda Bookshop Plot’ and ‘The Englishman Called Hugh’ was followed by a book signing.

Author’s Prologue

The art of conversation, some say, is dying. Go into a restaurant and you will see couples sitting there silently texting. I asked one couple recently if they were texting each other. The lady blushed. Go into a pub and you will see people staring at TV screens. One where I live has at least six massive screens, two in the garden. Customers stare miserably at them. In other bars, loud music blares out, making conversation, other than a shouting match, impossible.

However, I do know of taverns where the “craic”, the enjoyable conversation, still flows freely. The Shaggy Dog Story can form part of the fun. Stories can range from the obscene, to the sad and the totally absurd.

They nearly always end in a pun or punning phrase – there are many types – based on a distorted saying or catchphrase. They say the pun has been an essential part of English literature since Beowulf and before. Shakespeare was not averse to the odd one: “Now is the winter or our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York.” (Richard III, Act I, Scene I). “Puns are the highest form of literature.” [!] (Alfred Hitchcock, TV interview with Dick Cavett, 1972.)

The stories in this book cultivate, in the main, the Absurd. One definition of the Absurd is that it is about the dysfunctional relationship between human beings and their world. A sense of the Absurd comes from a feeling that things are just not working properly. The news was filled recently for days with stories about a singer song-writer I had never heard of.

The Spanish call shaggy dog stories “cuentos absurdos”, absurd stories, the French, “histoires grotesques” or “histoires sans queue ni tête”, stories without head nor tail. The English expression “I can’t make head nor tail of it” must be related to the latter.

Literature of the Absurd has a strong presence in many cultures, especially those of English-speaking countries. Eugène Ionesco, Harold Pinter, Luis Buñuel, Camus (at school I was influenced by Camus’ concept of absurdisme), Sartre, Stoppard and many others have exploited it. Children still read the “literary nonsense” novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, often shortened to Alice in Wonderland (1865) by the English mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who used the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. My generation was brought up on the radio series The Goon Show. We were in that end-of-empire period in which old customs, habits, manners and ways of thinking were changing radically and were no longer appropriate. A friend of mine received one hundred pounds to buy a dinner suit before going out to Africa. He bought a pair of snake skin boots down the King’s Road instead.

A shaggy dog story involves considerable build-up and convoluted action, resolved with an anti-climax or ironic reversal that renders the whole story meaningless. It may, perhaps, be the humblest example in the literary field but it is vigorous in oral, anglophone story-telling culture. It rests on the teller and the listener having a shared sense of the ridiculous. Life itself, after all, can often seem ridiculous. Instead of feeling tragic about it, as Unamuno, and at times, Dylan Thomas did, another possible reaction is to laugh at its absurdities.

On reading this book, the reader will say to himself or herself “I have heard that before”. In many cases this will be absolutely true. The tradition of shaggy dog story telling relies on a stock of familiar, formulaic and well-worn situations, retold in different contexts. Their number is limited by the small amount of surprising and acceptable puns available. The author makes no apology for going down this well-trodden path.

My father worked in a displaced persons’ camps near Lecce in Italy during the Second World War. He used to tell this story. A man would stand up and say “Numero quarantaquattro” (joke number forty-four). His colleagues fell about laughing. “Numero nove, number nine”, he would shout. His companions beat the floor with their fists, roaring with laughter. “It’s not what you say, it’s the way that you say it that counts,” he told me by way of explanation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my immense gratitude once again to Dr Clive Mann for his painstaking proof-reading of these stories. He did far more than that. He corrected factual inaccuracies and suggested ways in which the humour could be improved.

I would also like to thank, for their inspiration and suggestions, the small army of old Africa hands, fellow aid workers from the sixties and seventies, who have kept in touch with each other on both sides of the Pond and the Wall and who hold the occasional reunion, either here in London or in the USA.

Finally, I would like to thank my son William Gurney for providing the cover for this book.

Contents

The Girl with the Glass Eye / The Dead Ringer of Rubaga / The Bell-Ringer of Montmartre / The Dust Devil Chaser of Amboseli / The Bowling Green Man of Entebbe / The Death’s Head Hawk Moth Man of Makerere / The Englishman Called Hugh /

The Fiendish Uganda Bookshop Plot / The Ghastly Soroti Coffin / The Giraffe Among the Twa / The Glutton of Namirembe / The Hills of Uganda / The Kampalan Clairvoyant / The Music Man of Kololo / The Lord of Nyamuliro / The Man with an Orange Head / The Missionaries of Bujumbura / The Naked Woman in the Kampala Odeon / The Nightmare on Makindye Hill / The Optometrist of Owino / The Original African Shaggy Dog Story / The Terrifyingly High Pier of Port Bell / The Sad Tale of Rwenzori Rory / The Talking Dog of Kinsenyi / The Tin Man of Nakasero.

The Dead Ringer of Rubaga

The bell ringer at St Mary’s Cathedral, Rubaga, in Kampala, retired after decades of service, so the priest placed an advertisement in the Uganda Argus for a new campanologist.

Kabaka Mutesa I Mukaabya Walugembe, the thirtieth Kabaka of Buganda, who reigned from 1856 until 1884, once maintained a palace where Rubaga now stands. He had abandoned the hill after the palace burned down following a lightning strike, giving the land to French missionaries, the White Fathers or “Wafaransa”, as the locals called them. The Anglicans were put on Namirembe Hill, at a good distance from the Catholics, so that they could not engage easily and publicly in fisticuffs.

Anyway, the next day, Claude Pearman, a Bedfordshire man and a Philosophy and Religious Studies lecturer at Makerere University, arrived to apply for the vacancy. The advert had said, “No paperwork. Just turn up”. The priest couldn’t help noticing that his arms were in plaster and that each arm was supported by its own sling.

“What’s wrong with your arms?” he asked Claude.

“I broke both of them during a rugby match between Makerere and Jinja. I tried to tackle a huge soldier from the barracks. Said his name was Amin.”

Claude was a keen rugby player as well as an enthusiastic bell-ringer and an excellent philosopher to boot. He didn’t tell the priest but he had severe doubts about some aspects of Christianity but he loved the sound of bells, the camaraderie and the sheer physical exercise of pulling on the ropes. He comforted himself, when doubts assailed him, by rehearsing the steps of Pascal’s ‘Wager’ on which he had written several papers.

The steps in Pascal’s thinking rang like pure bell chimes in Claude’s head as he stood inside the cathedral. He remembered, he wasn’t sure why, the beautiful harmony, the symphony of sound, of the churches of his beloved native county. Dozens of churches across Bedfordshire lent their voices to a rich carpet of sound in the still, balmy air at Christmas time. His mother had wanted him to become a vicar but he had rebelled.

“How are you going to ring the bell with arms like that?” the priest asked Claude abruptly, jolting him out of his reverie.

“I can do it, believe me,” said Claude He was desperate to secure the position.

“I bet you can’t,” said the priest.

“I bet I can,” Claude replied. “Let me show you.”

They climbed up the many stairs to the bell tower. Claude leaned against a wall, then started running at full speed towards the largest bell. When he struck the bell with his face, it made the most beautiful sound that the priest had ever heard. The sound could be heard not only all over Rubaga Hill, it could be picked up on all of the seven hills of Kampala.

Claude then ran at another bell and with the first bell still resonating, the harmony was magnificent.

He ran again at a third bell, but this time he slipped and instead of hitting the bell he skidded out the bell-tower, through one of the slats, and fell to his death on the ground below.

The priest ran downstairs. A crowd had formed around the dead man’s body.

“Who is this mzungu?” the crowd asked.

The priest replied, “Well, I don’t know his name, but his face rang a bell.”

Robert Gurney, Absurd Tales from Africa, Cambria Books, 2017

The Bell-Ringer of Montmartre

“It’s a miracle!” the cry went up from the crowd surrounding Claude’s body. Despite being pronounced dead by the ambulance men who had arrived, one of his feet was seen to move. Claude had fallen on to a bush in a freshly dug flower bed.

Father Mukasa was delighted. He took pity on Claude and welcomed him into his church. It took Claude months to recover. He was left with such bad injuries, though, that ringing the church bells was out of the question. Father Mukasa encouraged Claude to ring the small bell that is traditionally rung at key moments in the Mass.

Indeed, it was during Mass that Claude glimpsed his way forward. He spoke to Father Mukasa about it and they agreed on a plan. The Church would finance a course on hand bell ringing for Claude. An expert was flown in from London.

Claude took to his course like a duck to water. His worked his way through the syllabus in no time at all: Four Bells, Six Bells, Weaving, Echo, Gyro, Malleting, Martellato, Plucking, Shaking, Singing Bell, Tower Swing, Thumb Damp: Claude was in seventh heaven.

The Vice-Chancellor of Makerere made the charitable decision to allow Claude to continue on full pay as a research fellow until such time as he was back on his feet. Some muttered, “That will be never”.

And so his life continued happily in Kampala. He was often to be found in Rubaga Cathedral. Father Mukasa allowed Claude to practice in the vestry. For the priest it was more than an act of charity. He genuinely liked the Englishman. Claude combined an endearing light-heartedness with an engaging seriousness.

However, all was not well in the cathedral. Complaints were beginning to surface that Claude’s hand bell ringing could be heard during some services. Father Mukasa asked Claude to tone it down a little but Claude was now so into his new pursuit that things eventually came to a head. Following a phone call to the Head of Music at Makerere, and without Claude being aware of what was going on, he was offered space in one of the tiny practice booths on campus. Students used to gather below the window to enjoy his sweet chimes.

Another cloud began to form on the horizon. One or two bad-natured students began to complain that their access to the booths had been affected by Claude being there too long each day. It came up at the departmental board of studies and, by a narrow majority, it was decided that Claude had to go.

He felt lost. He took to wandering around the city in search of venues. He had by now acquired a suitcase specially designed to take a rack of bells. The only places he found that were vaguely tolerant of his hobby were bars.

He first of all set up shop in the Makerere staff bar. The majority of Claude’s colleagues were tolerant of his eccentricity. He would ensconce himself in the games room or in a corner of the bar. Staff would smile as the sweet notes rang out.

Again, he faced another obstacle. A couple of writers, one American, the other from Latin America, were planning a joint talk on the theme of ‘The Dignity of the African Good-Time Girl’. They liked to explore such topics. It gave them scope to do field research and data-gathering. They encouraged their students to go out into the city to gain first-hand experience. They were discussing whether the girls they were researching were proto-feminists when their deep thoughts were interrupted by the quiet sound of bells.

The American stared icily at Claude. Claude became aware of the fixed stare coming from the end of the bar. At first, he shook his head. The person did not seem real. He looked like one of those personalised cardboard cut-outs that were becoming popular in Kampala. There was one of a glamorous air-hostess in the East African Airways office in the city centre. A fellow lecturer had purloined it one day by simply walking out with her with his arm round her. She looked so real that nobody raised an eyebrow.

The glaring became more intense. Claude could almost feel the reflected light sparking like electricity from the American’s round, steel-framed glasses. There wasn’t the slightest twitch of a muscle in the cold, hostile face. At that moment, all Claude was aware of was this menacing, white, emoticon-like white circle emanating ill-will towards him. He packed up his bells and left.

He decided to go and drown his sorrows in Okello’s Bar. He took a taxi to the outskirts. Okello’s Bar was no more than a tin shack built on bare earth. The earth was swept clean each day and had acquired a shiny look. Claude liked it there. It felt real and Okello liked to welcome wazungu. It wasn’t just that he liked their company, which he did, they also made him feel a little safer. Okello showed Claude a machine-gun that he kept under the counter. “They’ll try to come and get me one day,” he explained to Claude. “I’ll be ready.” Claude never asked who they were. He wasn’t sure but he assumed Okello meant the Baganda. Okello was from the north.

Claude ordered his Tusker and opened up his case. At first, Okello was fascinated by this phenomenon. He liked Claude’s version of ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ and Bing Crosby’s ‘White Christmas’. Englishmen often surprised him with their interests. One of his customers, Alex, a Scotsman, would sometimes fetch his bagpipes from his car. It was good for business. Word would get around and the bar would fill up. Claude began to frequent Okello’s bar more and more. Initially, Okello saw that his sales were going up but, after a while, they began to go down. Customers were growing weary of Claude’s bells. Okello asked Claude politely but firmly to take his bells elsewhere.

He installed himself in the Gardenia but soon the girls were complaining that their enjoyment of the Animals’ ‘House of the Rising Sun’ and Millie Small’s ‘My Boy Lollypop’ was being ruined by the sound of Claude’s bells. The owner tried turning up the volume of the jukebox but it didn’t work. He asked Claude to move on, in spite of the fact that Claude was now consuming large quantities of Nile and Tusker.

Claude tried the Rugby Club. He didn’t last five minutes. He told me that the mocking words of the song “Why was he born so beautiful, why was he born at all?” were still ringing in his ears as I dropped him off at Mitchell Hall at Makerere.

His next port of call, and what turned out to be his last in Uganda, was the City Bar in the very centre of the town. Claude was totally compos mentis. He knew that his music could irritate people but he just had to practice to keep himself sane. Babu, the owner, was very liberal, very compassionate. He invited Claude to sit out on the veranda at the front of the bar, overlooking Kampala Road. He calculated that the roar of the traffic would mitigate the effect of Claude’s bell-ringing.

Now, the country was entering difficult times. Tribalism was raising its ugly head at all levels. The terrace of the City Bar was no longer the safe haven for the weary, the thirsty and the lost that it had been in better times. For example, Melvyn, the barman at the rugby club, who appeared constantly to wear a triumphant smirk on his face – it was, in reality, a product of his embarrassment at his physical ungainliness and his lowly social origin – made the mistake one day of raising his beer glass and grinning at a passing lorry load of soldiers who were clearly from the north. The lorry screeched to a halt. Melvyn dashed for the door at the back, got into his car and shot off before the offended soldiers could find him.

A similar thing happened to Claude. He was tapping away on his bells when a passing Land Rover stopped and an angry officer, a colonel, stepped out. I am not sure what Claude was playing. I have heard that it was ‘Ding dong bell, pussy’s in the well’. Whatever it was, the soldier heard what he thought was either a subversive tune or an insult. Babu stepped in, placing himself between Claude and the angry colonel. Claude began to pack his case up rapidly. He felt slightly annoyed when he saw Babu tapping his head and nodding towards him.

It dawned on Claude’s friends at Makerere, myself amongst them, that Claude was no longer safe in Kampala. The former kind atmosphere of ‘live and let live’ was fast disappearing. The dictator was beginning to flex his muscles. Even London, it was rumoured, could be reached by his tentacles. Stories were circulating that the king, who had gone into exile in England, may have been poisoned. Paris, it was felt, was becoming the only safe destination for those fleeing the death squads. The staff at the embassy there, who had been in post since the early sixties, had somehow managed to prevent infiltration by hit men. I suggested that Claude be flown to Paris. This was agreed. The authorities at the university said that his salary would be paid to him there, at the Embassy, until he found suitable employment.

Claude loved Paris and Paris took to him. He would sit on a folding chair in the Place du Tertre and play his bells to passing tourists or to people having their portraits done. Coins mounted up in his hat. His crowning achievement was to play in harmony with the bells of the nearby Basilica of the Sacré Cœur. He became known to Parisians as “le Sonneur de Montmartre” and appeared quite often on French TV.

Fate is a funny thing. Claude loved to stand on one of the bridges that cross the Seine by Notre Dame Cathedral. He loved to contemplate the sheer beauty of the building. One New Year’s Eve he was there. You could just hear his bells tinkling above the roars of the crowd as they welcomed in the New Year. Rockets went up in the air and the crowd gasped in awe, falling back as they looked up. Claude, who had been drinking heavily, lost his balance and fell over the parapet, still clutching his rack of bells. As he sank into the depths of the river, some say that they swear that they saw a smile on his face and that they could hear him singing: “I’m ringin’ in the Seine / Just ringin’ in the Seine / What a glorious feelin’ / I’m happy again / I’m laughing at clouds”. Then, nothing: Claude just disappeared into the icy water.

Robert Gurney, Absurd Tales from Africa, Cambria Books, 2017

The Bowling Green Man of Entebbe

To Steve Lord

Bob Tell and his wife loved playing bowls. The type of bowls they specifically adored was English lawn bowling.

Bob had grown up in a house that overlooked a beautifully manicured bowling green in Luton, England. He had spent many an evening as a child leaning over the fence looking at the bowlers. He loved the polished wood of their bowls and the sound of bowl striking bowl. For him it was a sort secret language: click-click-click, click, the language of permanence. To him the essential English evening scene was a windless, sunlit green where men and women in whites stood stock-still. It represented stability and respectability, civilisation, Man’s mastery of Nature.

Later, when he grew up he was allowed to join in, despite the fact that he was years younger than the other bowlers.

Then, one day, he was told he had to go to Africa. He was a civil servant and the newly independent country of Uganda needed his area of expertise: agriculture. He was to advise on the best seeds to use in Uganda.

He and his wife, Mary Tell, moved into a bungalow in Entebbe, a short walk from the President’s office. Bob liked Entebbe. It was a green and pleasant place. Rain fell regularly on its lawns every afternoon at three. Life was good. The restaurant of the Lake Vic hotel could scarcely be bettered anywhere in East and Central Africa. He understood how Churchill could have called Uganda “the pearl of Africa.” But Bob missed his bowling green.

It was then that he decided to do something about it. He decided that what Entebbe needed was a bowls club. There were enough Englishmen and women working in the government offices to make it viable.

He rented some land from a chief near the lake’s edge, using money he had inherited from an uncle. He set about flattening his field. He employed a small army of men with wheelbarrows to spread good topsoil garnered from swampy areas that had been drained in Kampala. His mouth watered as the rich black earth went down.

He then had to decide on the grass seed. The grass in Uganda seemed to him to very hard in comparison with the softness of grass in England. He knew through his training that there were grasses that thrived in the cool season and others that were better suited to the warm season, not that these were very distinguishable in the micro-climate at the side of the lake.

Once the field had been flattened and levelled he divided it up into squares. The most successful square would become the green. In one he planted warm season grass seed that was tolerant of drought, i.e. it needed less watering. Water was not his main concern in Entebbe, though, because of the powerful rain storms that built up each day over the lake.

He planted Bermuda grass that, he knew, was quite disease-resistant. He had heard from old Africa hands in the Kampala Club that they tended to use this seed for their lawns. He tried St Augustine grass but realised that it was rather thick-bladed and needed a great deal of water. He experimented with Buffalo grass, very drought-tolerant and needing lots of sunshine. He did not have much shade at Entebbe and thought that, perhaps, this might prove to be the one. He seeded square after square, one with Zoysia grass, another with Bahia grass, the latter being able to resist most insect attacks. Entebbe was plagued with insects at that time. He tried Kentucky blue grass, fescue grass, tall fescue, which is hard-wearing, red fescue and perennial rye-grass. He was coming to the conclusion that it was this last one that would make the best sward for bowling.

Having set the experiments in motion, he knew he had to just sit back and wait for the results. In one or two cases these could take a year or more. No matter, he installed himself in a wicker chair at the side of his patches and just sat there under a tree smoking his pipe and watching the grass grow.

He became restless. The old urge to play bowls began to reassert itself in earnest. His discussed this with his wife Mary. She understood and approved his plan that they should travel, in their holidays, to established bowling greens in other parts of Africa.

First of all they ventured out to Nanyuki but Bob was not entirely satisfied with the smoothness, or lack of, of the turf. They decided to venture further abroad. They found one that he came to love especially, the bowling green in the grounds of Cathedral Peak Hotel in the Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa.

They found another they liked, the Lawn Bowls Club in the Clifton area of Cape Town. Bob was in his element on the South African greens. He didn’t really want to go back to Entebbe but, needs must, he and Mary always returned before the end of their holidays.

During one holiday a small clubhouse had gone up, on Bob’s instruction, next to one of the squares of land back in Entebbe. This large shed – it wasn’t much more than that – became like a second home to Bob. Now and then he would, with Mary’s permission, spend the night in it so that he could be up at dawn to put the sprinklers on his rye-grass green. It wasn’t ideal but it was the best grass he could come up with. His green was passable.

The years went by and Bob slowly developed an archive in the “club house”. In it he kept the records of games: who in Entebbe had got nearest to the jack in 1967, that sort of thing. He and Mary also kept the correspondence they had had with clubs in other parts of Africa. Bob was proud of his archive. It contained newspaper reports of the victories and defeats of the sides he had played for, particularly in Cathedral Peak.

One day the club burned down. No one knows what caused it. Some say that a dispute about the land lay behind it but Bob would never speak about it. He was heart-broken. The fire brigade had cut across his pride and joy, his rye-grass green, carving deep ruts in its surface. It was as if all he had worked for had been defaced, desecrated. And the fact that the paperwork was destroyed in the conflagration means that posterity will never know now for whom exactly the Tells bowled.

Amazon review:

“If you want something to lighten your day, and in such an accessible form. these incredible, overwhelmingly farcical tales will not disappoint you. I heartily recommend.” 5 stars.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Absurd-Tales-Africa-Gurney-Robert-ebook/dp/B06XDCPG2D

The Terrifyingly High Pier of Port Bell

He was a nice chap. We called him “Clint”. That was irony. His real name was Dave. He was a mild-mannered man. He was in my MA in Comparative African Literature class at Makerere. I was specialising in the poetry of the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries of Africa. Eventually both he and I got good jobs lecturing in African Literature, he in the States, I in London.Time and places change people. I almost went to Orange County but they were running out of young men for Vietnam. He went to Connecticut. We got back in touch recently.

I remember his landlady, Mrs Fisher. She was a smiley lady who was always sitting down. Her skin looked glaucous. It had a shiny, not dull, greyish-blue colour. “She loves her gin”, I was told.

Dave shared the flat with Miles. Miles was not his real name. That was Brian. Brian had become Miles at school, through a strange process of alchemy then in vogue. They were both Londoners but seemed as different as chalk from cheese. I was more friendly with Miles than with Dave. Dave was more reserved. Miles was out-going.

I remember the flat that Dave and Miles rented from Mrs Fisher. It was not far from the back door of the City Bar. She was one of the few Europeans who rented out flats. It was old and damp. I remember a big barrel of beer in the middle of the veranda floor put there for a party. The floor bowed and looked as if it was about to cave in! Looking back, Kampala was a great place. I know I benefited hugely from it.

I knew Miles better than Dave. Miles, as we always called him, used to rag Dave. He, we, as I have said, called Dave “Clint”, after Clint Eastwood, I suppose. He wasn’t like Clint Eastwood at all.

(Dave tells me now that he was called Crint, not Clint, after a very camp and effeminate man played by Peter Sellers in ‘The Goon Show’, a type of official, one Jim CrintFlowerdew. I do not remember Clint or Crint as being effeminate. It was all part of the ribbing.)

Be that as it may, Miles implied that Dave was softer than he was. Miles could be competitive but I suspect that Dave gave him as good as he got. He didn’t do it in public though. I felt Miles was slightly cruel to Dave. Dave suffered in silence when Miles pulled his leg in front of others. Miles used to do it to me, perhaps, but I ignored it, which he liked. My ego was a little bit stronger than Dave’s was then. I was also slightly older. I can’t remember if Dave had been to public school. I imagined then that, like me, he hadn’t. Miles had strong self-belief. I think this, curiously, was good for Dave. It made Dave say to himself that he was all right too. Miles didn’t do it so much, the putting down, with me. I felt that Dave was possibly hiding his light under a bushel. He was a bit shy and was wary of The City Bar, although I think he liked a half with me and Danny and others in the humbler pub, the International Bar, at the foot of Kololo Hill near where our tutor, Dr Aurora Chaleco, from Trinidad, lived. Dr Chaleco and I exchanged emails not so long ago. She’s in Cuba now.

I am trying to remember Dave’s girlfriend’s name. I have a feeling he had a girl in London. Her skin didn’t look too good. She wore heavy make-up. Yes, she came out to Uganda to visit. This clipped Dave’s wings a little.

Miles used to say “Naff off, Clint”, or something stronger, to Dave all the time. Dave would smile. It was all a bit Top Gear-ish, Jeremy Clarkson versus James May. I felt Dave was wary about being perceived as “one of the lads”. I have a feeling respectability mattered to him. I could go on for ages about that.

I remember snatches of conversation:

Me: “We are off for a pint! Coming?”

Dave: “Er, I have that essay to finish for Agnes [Dr Agnes Shefford].”

Me: “Oh stop being a goody-goody! Blow Agnes!

Come on, Clint!”

Dave: “Tomorrow.”

To be honest, I didn’t like the way Miles treated Dave. I often felt like telling Miles but I didn’t, concluding that it was none of my business. He was always going about “blooming Simpson”. He may have said, “What a drag he is. Can’t get him to do anything” – that sort of thing. It was a strange relationship. I often asked myself why Dave put up with it. I concluded that he and Miles wanted a flat in the city centre, away from the campus, and could only afford it by pooling their resources.

Miles was into glamour – Hilary Highgate. In later years she and he would visit me and my wife in our flat back in north London. She would collapse on the sofa and ask for a cup of tea, gasping “My back!” High maintenance. No, that’s not fair, she did have a bad back. Miles seemed hen-pecked. He was always rushing about on some errand or other to please her. I have a feeling he was vulnerable. As you know, Dr Ferdinand, the Comparative Literature Professor, loved him because he was working-class and had been a scholarship boy at a leading London public school. The social experiment had been a success in Dr Ferdinand’s eyes. She, Dr Aurita Ferdinand, from Río Muni, Equatorial Guinea, was left wing. Her family had strong upper-class ties with England but that’s another story. I have a feeling it had stressed Miles out going to that school. It did his health in in the end. Dave was “all at sea”, I suspect, about what was going on, inside Miles’s head. Discretion was the greater part of valour, for Dave. Miles went on to do stocks and shares as a side-line, which I think was very bad for him, for his nerves. I had a suspicion Miles needed Dave to boost his ego. I guess Dave was a bit bemused by this. I suppose Miles had the public school boy’s need to feel, and be seen to be, top dog. But he didn’t do it with me. A job came up in Mozambique. I told Miles I was applying. I felt I had a strong case. He hadn’t heard about it. He applied without telling me and was called for interview. I felt miffed about that and our friendship cooled a little thereafter.

I dread to think what Dave thought about me. At that time I couldn’t have cared less what people thought. I was into carpe diem, grabbing hungrily at each second. I think it annoyed our African Linguistics lecturer, Agnes, that I was so unconcerned about what she thought. She concluded, “not public school material”, I am sure. I was never invited on her Makerere Madrigal Choir tours ofLourenço Marques, or Maputo, as it is now called. Mind you, I couldn’t sing. You should have seen Agnes’s face when I walked in for the interview for the Chair in Accra, or was it Abuja? She said, with a self-satisfied, false-sincere expression, “Sorry. Wheels within wheels, you know.” She and I clashed over Annie. There was talk of careers in MI5 or MI6 and even the Ugandan Secret Service – there were so few modern languages graduates specialising in Africa then. I was totally turned off by the idea.

Agnes offered me ‘Thieves Slang in Luanda’ and ‘The Influence of North Africa in The Gypsy Language of Andalusia’ as possible PhD topics. She was trying to get rid of me, I concluded.

I have a feeling Dave felt that it was necessary to keep his head down, not to blot his copy-book, which was all too easy in small town Kampala, as it was then, where nearly everyone knew where and with whom nearly everyone else was sleeping. I have a feeling Dave felt that he had possibly stuck his neck out too far by moving into a trendy flat. I was envious. It was cool. It made Dave careful about what he did and said. He worried, I suspect, that people might report anything negative he might have said. I can hardly remember Dave saying anything now. This was very sensible, I felt. Anyway, it is very English to be self-effacing. God knows how Dave managed to cope with in-your-face, “my son’s going to be the next president”, America. In Africa and the UK we knew that there was not much on offer and that there was no need to strut one’s stuff on the stage of life. It would not lead anywhere unless you were born into the right circles. There was Percy, the Right Honourable Percy Chiswick, whose area of expertise was the Literatures of Anglophone Africa. He became the UK’s man in the Middle East. Blithering idiot. And Agnes! Well! I have just written a novel in which some of this comes up.

I was fascinated by Miles because of his combination of working class lad and upper middle class schoolboy. I don’t think he was at ease with the in-set on Nakasero. Strangely, I fitted in with the “nobs”. Times were a-changing. All that class stuff was beginning to crumble. I have a feeling Dave was nervous about moving into the new areas that were opening up. He clung to his childhood sweetheart: “And always keep a-hold of nurse, for fear of finding something worse”. I found them, the posh set, fascinating. What they were doing in Kampala, I don’t know. Many had ties with Kenyan settlers. There were the renegade daughters of conservative London entrepreneurs, like Mary of the famous British newspaper family. It was the world of A level English novels, in pockets. I tumbled into them. Don’t ask me how it happened but I had a classy accent. Miles did too, to some extent, but you could hear the Cockney underneath, both in his intonation and the structures. Hilary adopted a Mockney manner, a rough way of speaking, as if trying to hide her middle class origins. Miles was not into playing the field. Hilary didn’t know what to make of me really.

Miles had a mixture of working-class aggressiveness – if you are at the bottom of the pile you have to have it – plus a public school bossiness and assertiveness. If you are on top you have to fight to preserve your power. Call it self-confidence, if you like, or arrogance. Miles had to be right (almost) all the time. That’s what they teach you. Dave and I were, I suspect, lower-middle class, at least for a while. I liked to boast that I was working class but I am sure I was not a very convincing specimen in my jeans, Harris tweed jacket and suede shoes. We tended to keep our heads down and work hard, rarely venturing to raise them above the parapet. I did that a bit more than Dave, perhaps, when I parodied Dr Ferdinand, the Prof, using her phrases, “it seems to me” and so on, at the away day conference centre that the university owned in the mountains of Kigezi. Kigezi coffee! I still remember it. God knows how I got away with the parodying. I probably didn’t. I could be wrong, by the way, about Dave’s social class then. I must ask him.

I often felt Dave didn’t look well. Miles and I would go off jogging each day. He was glowing with health. I was too. He would often comment that Dave would not venture out into the fresh air, into the sun. He did look pale, did Dave. I put it down to bad food. I concluded that he and Miles were spending too much of their money on the rent. Perhaps Hilary – she was wealthy – cooked Miles some fillet steak, some filet mignon, in her digs.

One day Miles and I decided that Dave needed to get out more. A rich student called Kenneth Sinclair-Otieno kept a rather spectacular rowing boat in a lock-up down by the jetty in Port Bell, where the flying boats used to land. He called it a Thames wherry. It was in fact built to an eighteenth century design. It needed more than one person to get it going. We persuaded Ken to lend it to us. Our friend Dave needed to exercise and breathe in some good lake air, we argued. He needed to get out of his gloomy flat. Ken consented.

After considerable arm-twisting, Dave agreed to come rowing with us. The lake was choppy and we pushed the boat on its trolley to the end of the jetty. As we went past the plaque that said ‘Port Bell Pier 3730 feet’, I saw a look of alarm spread across Dave’s face. His jaw dropped and he went white. His head began to spin and his eyes glazed over. He felt he was going to faint.

“Right, Dave, this is the moment of truth. You launch the boat,” Miles said.

Dave peered over the edge. He pulled back.

“I can’t do it!” he cried, “I just can’t”.

“Why on earth not?” Miles barked angrily.

Dave replied with a sheepish grin: “It’s a long way to tip a wherry!”